Maan Ka Khawab…

“…Samajhti Hai Tu Ho Gaya Kya Issay?

Tere Aanasuon Ne Bhujaya Issay!”

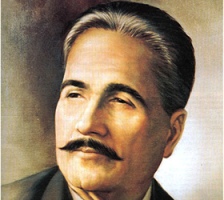

-Muhammad Iqbal (rahimahullah), Maan Ka Khawab

Yesterday feels like a dream now. Exhausted from last night, I barely had the energy to pray ‘Isha by the time we finally arrived home. Seated on my recliner with my legs folded under me, I refreshed one app after the next. Gmail. Facebook. My mom’s Gmail. Facebook. Nothing’s changed. No response from Mr. Rishta on my mom’s account. No haunting little red notification. No one emailed me. Good. Less distractions anyway. Better get to praying ‘Isha. If I delayed it any longer, I was afraid I would be too tired and it might no longer be counted as worship–it would simply be reduced to a solitary act of movements and empty words. No. I wanted my worship to be to mean something and to be accepted. I needed it.

On the drive home, passing each successive street lamp set against the backdrop of the night, I looked onto the ones up ahead and thought about how deep it would be if that image could be used as a metaphor for life and the human experience. And it wasn’t out of nowhere that this idea came up. As my dad drove along, he was discussing with the three of us the powerful and well-know poet philosopher (especially among the South Asian and Iranian community), Dr. Muhammad “Allama” Iqbal. More specifically, he was telling us about how the man used his poetry as a release from the darkness in this world, to shine a light for himself and for others. My dad says his poetry was also a kind of “translation” of the Quran. I remember my teacher, Sh. Khalil (May Allah have mercy on him) saying something similar about Rumi’s Mathnawi.

On the drive home, passing each successive street lamp set against the backdrop of the night, I looked onto the ones up ahead and thought about how deep it would be if that image could be used as a metaphor for life and the human experience. And it wasn’t out of nowhere that this idea came up. As my dad drove along, he was discussing with the three of us the powerful and well-know poet philosopher (especially among the South Asian and Iranian community), Dr. Muhammad “Allama” Iqbal. More specifically, he was telling us about how the man used his poetry as a release from the darkness in this world, to shine a light for himself and for others. My dad says his poetry was also a kind of “translation” of the Quran. I remember my teacher, Sh. Khalil (May Allah have mercy on him) saying something similar about Rumi’s Mathnawi.

This was another one of my dad’s mini-alternative-history-lessons-in-the-car moment. I relished the moment. The conversation was sparked by my own curiosity about what my brother had been discussing with Haroon Moghul earlier in the day during a lunch break at the Muslim Protagonist. A part of me also wanted to get rid of the tension in the car after some justified fatherly anger towards him. According to my brother’s rough recollection of the conversation, he learned that Dr. Iqbal was a proponent of the idea of a decolonized India, but his authority in poetry-philosophy was used as propaganda for a more destructive cause, and that was the very division of India and Pakistan (and eventually, Bangladesh). A divided India, however, was not his vision.

My father insisted we read his work. He reminded my brother, now really seeming to dig Allama Iqbal, that two years ago he had tried fruitlessly to persuade his interests towards the doctor’s work. A classic, yet subtle, fatherly I-told-you-so. He insisted again that we read the English translation, as his work had been translated into many languages. A final insistence, that we look up his work online, and I had to start Google-ing. I wasn’t aware of the online English translations (although, how could I not be when everything is online). So he started jogging his memory for the first lines to a poetic dua.

My father insisted we read his work. He reminded my brother, now really seeming to dig Allama Iqbal, that two years ago he had tried fruitlessly to persuade his interests towards the doctor’s work. A classic, yet subtle, fatherly I-told-you-so. He insisted again that we read the English translation, as his work had been translated into many languages. A final insistence, that we look up his work online, and I had to start Google-ing. I wasn’t aware of the online English translations (although, how could I not be when everything is online). So he started jogging his memory for the first lines to a poetic dua.

Lab pe aati hai dua…

A prayer comes to my lips. Wikipedia had a couplet-by-couplet translation. I read it out loud to everyone in the car, feeling each urdu transliterated word with all of me as it rolled off my tongue, into my ears, and then strummed something inside. Urdu is beautiful. His poetry was on another level. If only I knew Urdu.

Maybe it was the exhaustion speaking, but no sooner had I read this poem, my brother began to apologize for upsetting dad. A private peace descended in the car.

At the end of the ride home, my dad suggested another one of Dr. Iqbal’s poems. “Maan.” Mother. Touchy subject–always. Always afraid that if I read something I’ll start balling or that my heart will hurt from guilt that I don’t act justly with her. I couldn’t find a wikipedia article like I did for the last one, so I settled for whatever else the internet had to offer. The translation I found could do no justice. But I read anyway. If only I knew Urdu. I read this one to myself this time. The imagery left me with mental goosebumps. Dr. Iqbal was on another level.

I read it again this evening. My sister and I sat in my room as I read out the same poem in Urdu, feeling each sentence in my mother tongue. We discussed our interpretation of the imagery in the poem and, to our surprise, came up with three different understandings. Here, I offer my poor, second-hand translation.

A mother’s dream: She sees herself in a dark place, has no path in front of her. Filled with fear, she musters up the courage to take a few steps when she notices a line of little boys dressed in emerald moving about to God only knows where, each holding a lamp.

Out of this crowd she recognized her son, slower paced than the rest and holding a lamp which is unlit. She calls to him, lamenting about how he has left her, how she cries every day out of agony from the separation. He tells her that her tears do him no good, pauses, turns his lamp towards he and says,

“Do you understand what has happened to this?

Its light was put out by your tears.”